|

“Given Freedom, I Can Write Good Music” - Part

1

Interview with Guy Farley conducted on 3rd March 2012 in Sphere

Studios, London

by Stephan Eicke

Stephan

Eicke: Guy, when we first met in late

October 2011, you mentioned that you had just finished

recording your music for the new caper-movie “The Hot

Potato”.

Guy

Farley

: Yes, but I haven’t finished mastering

it yet because I haven’t got any time to do it but it’s the

next thing I’ll do. The score is about to be put into a

soundtrack-order and I like to do this work myself because I

want to make sure that it

also makes a good listening-experience. “The Hot Potato” is a

very generic score because it has a sound from the 60s in the

style of John Barry or Henry Mancini. I loved writing that and

I knew what I was writing. I remember saying to the director

“If we were in 1968 and you would got John Barry to write the

score, that’s what I want it to sound like.” And the director

was absolutely crazy about that idea and let me do my thing. make sure that it

also makes a good listening-experience. “The Hot Potato” is a

very generic score because it has a sound from the 60s in the

style of John Barry or Henry Mancini. I loved writing that and

I knew what I was writing. I remember saying to the director

“If we were in 1968 and you would got John Barry to write the

score, that’s what I want it to sound like.” And the director

was absolutely crazy about that idea and let me do my thing.

Q

:

I read the synopsis of the movie and it reminded me a

bit of “The Italian Job” with Michael

Caine.

G.

F.: Yes, although it’s

based on a true story. It’s about these men who find a very

expensive silver box which nobody else sees. In it they find

something covered in led, that looks like a hot potato. They

discover that it’s uranium. The first thing they think is that

they are going to die because they will get cancer and the

second thing is that they say: “We will die anyway, so let’s

try to make some money out of it.” It literally takes them

from seeing the local gangsters to Europe, thinking this is

not worth more than some thousand pounds and in the end they

look at 30 million pounds because they are so many interested

parties. It’s a fun movie and quite Pink-Panther’ish as well.

You remember the old car chase in “The Italian Job”? There is

a lot of that sort of humor in it.

Q

:

It sounds rather dramatic when they know they will get

cancer and that they will die…

G. F.: One

of the first things that you are faced with is when the older

man, played by Ray Winstone, says to his younger colleague “I

have some very bad news: this is uranium and it is used for

nuclear weapons. We have been exposed to it. It will kill us.”

You very quickly forget that because the film takes off and

you go with these ordinary guys who can have their lives

suddenly totally transformed by an enormous amount of money.

Q

:

So they know that they will die and despite that, they

try to make as much money as

possible?

G.

F.: Yes, for their

families. One of them is already married and the other one is

going to get married. However, you don’t really think about

that seriousness until the end of the film and remember that

this is all based on a true story.

Q

:

I never heard of that.

G. F.:

Neither had I.

Q

:

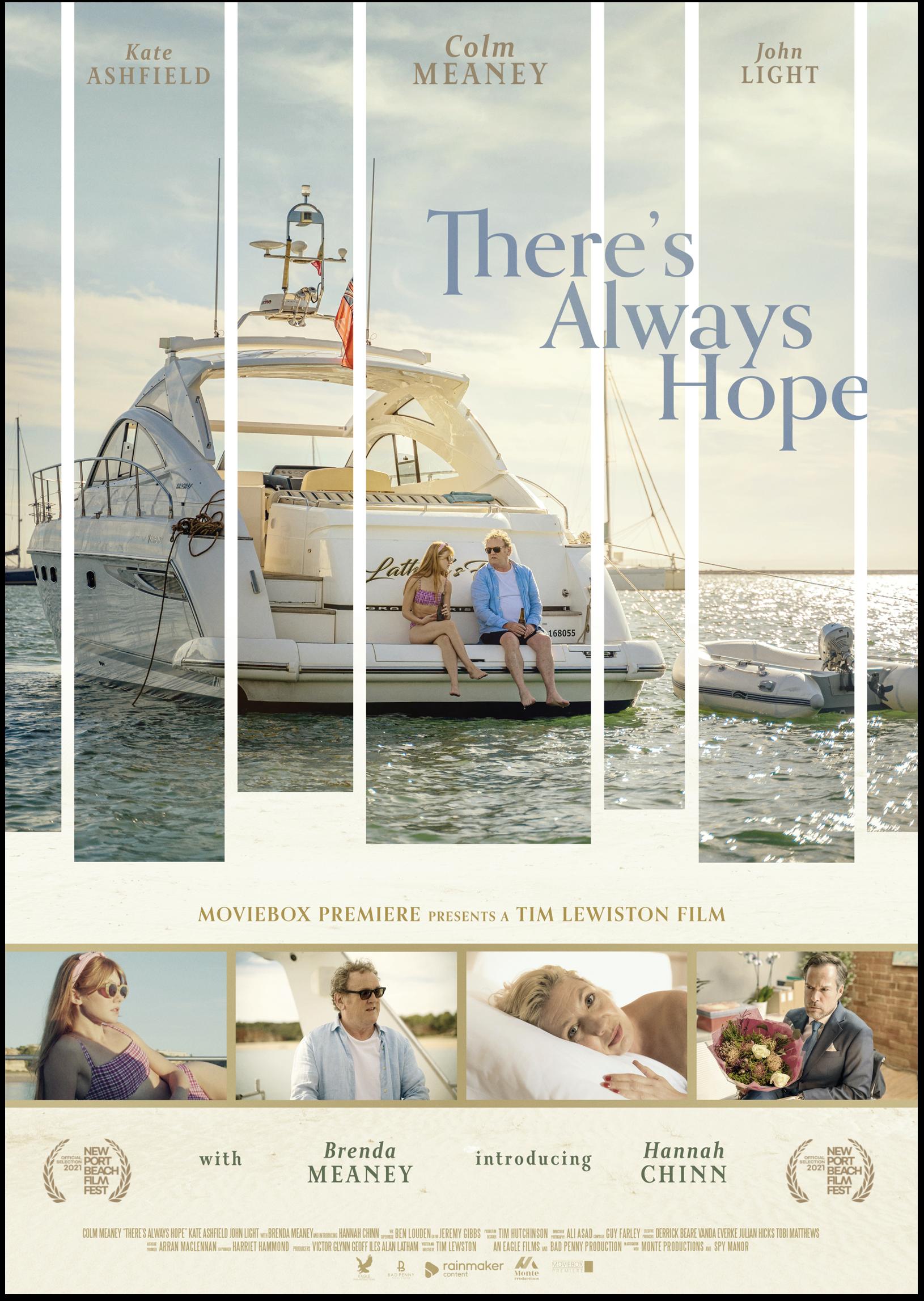

The director, Tim Lewiston, worked as a mixer at the

sound department of “Modigliani”. Q

:

The director, Tim Lewiston, worked as a mixer at the

sound department of “Modigliani”.

G. F.: Yes,

that’s how I first met him. He always wanted to graduate from

mixing and the sound-design and he always wanted to direct

movies. He had a lot of input on “Modigliani” and I enjoyed

working with him. After that, he worked on a movie which was

directed by John Irving and unfortunately, they had to work

with a Spanish composer. I would have loved to work with John

Irving but then “The Hot Potato” came about and originally,

they didn’t want to have a score at all but use songs from the

60s. As it often goes, you start with a certain idea and it

goes in a certain direction where you notice: “Hang on, we

have to tell a story here and we need the music to tell a

story.” So in the end, they decided to have an original score.

Q

:

Because of the fact that Tim Lewiston worked at the

sound department, he know how important music is and how do

handle it correctly.

G. F.: Absolutely! He fought all

the way to the end to make sure that we have a proper score. I

said to Tim: “There are a number of ways how you can do this

but the best way is to record the music at Abbey Road with the

best musicians that already played on the original scores from

the 60s. If we do that, it will elevate your film because the

sound will be amazing!” And even when people came to Tim and

said: “Maybe we should just use a few samples and a few

players”, he said very directly: “No, I want this to be the

real thing!” Tim did an amazing job as a director because he

pulled this movie together and made it all happen. He was

restless and fought for the money for the score. Making

independent movies is such a tough job. I don’t know how they

do it. It was very pleasant working with Tim because he is

very old-school. He loves great movies and great music, so he

was able to tell very quickly when he liked something or not.

He just knew it and that makes your life so much easier!

He used to say to

me that the highlight of his week was when I would turn up

with a new piece of music. Fortunately, they didn’t use any

temp-music because they couldn’t find anything that worked!

Q

:

This is surprising, because there are countless

jazz-pieces from the 60s.

G. F.: All

the pieces by John Barry or Henry Mancini were so strongly

identified with their own films they couldn’t use them as

temp-music. What a dream for a composer: no temp-music! It

means so many things! It means that the filmmakers are not

married to certain pieces of music, that they are not telling

you: “That doesn’t sound like the temp-music. Can you write a

piece like this?” It means that I’m free to write to picture

to tell the story as a composer. Another positive thing is

that when I do give them an idea on a piano as a demo, they

are very pleased to hear something real. I had times when I

was asked to score a movie and they had put music by Thomas

Newman on the film. I turned around to them and said: “Guys,

you have a complete budget of 30 000 Dollars on this movie and

you are telling me to write music that had a budget of one

million Dollars? Watch your movie without the temp-music. See

what it looks like without the aid of temp-music.” Temp-music

is a good and simple way to communicate between the director

and the composer: “I like that instrument! I like that chord!

Is that a major or a minor chord?” In that case it is okay

because it saves time. It is a problem when everybody gets

used to it. You can’t beat it. I have known directors who

said: “Can’t you just copy the temp-music?” That’s one of the

worst things you can ever hear! I remember working on a film

where I found myself sitting at the keyboard and looking for

the same sound that was heard in the temp-track instead of

looking for something new. I stopped myself and asked myself:

“What am I doing here? This is absolutely mad!”

Q

:

So you quit the job on that

film?

G.

F.: I didn’t quit the

job but I stopped myself and composed something different.

Imitating the temp-music is very unpleasant because you stop

being a composer. You wound up being a copyist or a

machine-man.

Q

:

I would like to talk with you about “Modigliani” in

detail because I think that it is still your best score. Is

that a compliment or would you prefer hearing that every new

score you compose is the best you have ever

done? Q

:

I would like to talk with you about “Modigliani” in

detail because I think that it is still your best score. Is

that a compliment or would you prefer hearing that every new

score you compose is the best you have ever

done?

G.

F.: No, because you have different experiences

on every film. Being realistic, every composer writes a bad

score. Every composer writes a good score. Every now and then,

a composer writes an outstanding score. There are reasons for

all three of those. On “Modigliani”, I worked with a

first-time director, who fell in love with a theme I wrote for

him. Originally, he didn’t want to hire or even meet me. He

wanted Elmer Bernstein to write the score. There was a lot of

hype about that movie and everybody was talking about awards

before I was even near it.

However, I knew the editor, who

said to me: “The director doesn’t know who you are or how and

where you work, so the best thing you can do is just writing

something.” I saw an assembly they had done for a promo and I

was so touched by what I saw – which was the scene where

Modigliani gets beaten up while his wife is waiting for him –

that I went back to my studio and wrote the theme immediately.

The problem was that I couldn’t just play it on the piano,

using fake strings. At that time, I was doing a string-session

with the ‘Sugarbabes’ and at the end of the session I said to

the orchestra: “Look, do you mind playing that piece of

music?” The orchestra was magnificent about it! They played

that bit of music, I went back to my studio and mixed it

before I gave it to the editor who said: “There is so much

emotion in it, I will put it over the scene where Modigliani’s

wife falls to her death because we couldn’t find the right

music for that part.”

They had a screening of the movie

afterwards and the director said: “What piece of music did you

use over that scene?” The editor said: “Somebody wrote

it.” “Someone wrote it? For that scene? Who?” “The name

is Guy Farley.” “Guy Farley? Where do I know that name from? I

want to see him this afternoon!”

We sat down, he looked at me and said:

“You are doing my movie! I was never moved by that scene until

I heard that piece of music!” From that moment on, everything

changed. I already had my main theme which was all I needed. I

was very moved by the movie. I felt the film and wrote the

music in this room where we are sitting now. The best thing

was, I was free to write it. I had the support of the

producers, I had the support of the director and I don’t even

remember the temp-music. They just let me write the score.

When I write what I think is good music, it’s when I am

completely left alone to write it. Given freedom, I can write

good music. It’s all emotional. Everything I write comes from

my heart.

Q

:

You were very lucky because in the scene where

Modigliani gets beaten up there is barely any sound at

all.

G.

F.: Yes and do you

know why? They took all the sound out because of the music.

They thought the music was more powerful. You can’t get a

greater compliment than that! The best screening I have ever

had of a film of mine was “Modigliani” in Los Angeles. They

had a big screening and it sounded amazing! I remember being

very proud because every cue was perfect. Very ofte n, I sit here and

reflect, thinking: “Oh my God, I could have done better than

that!” The other strange thing is that, when you listen to

your work after you had a great experience writing, recording

and mixing it, you start questioning it. “Is it really that

good?” One or two years later, you get back to it and think:

“Wow, did I write that?” I do believe that if I can write a

few good pieces in every score, I am happy. There are pieces

in a score that just do their job because you are writing the

music for a picture and I don’t sit here writing a work by Guy

Farley: This is me, this is my concept, this is my work, I am

answerable to myself and that’s it. I am working on something

and I think about what the producers and the director said. I

am reacting to the picture I am looking at but I am

considering all these things and my music has to serve the

picture. I know people who wanted to release my score to

“Tsotsi”, which is such a very strong film and so

character-driven that I was never able to breathe or feel

free. So when you listen to the soundtrack you will notice

that everything I did was supporting a scene. That was the

reason why I decided not to release it because I wouldn’t want

to listen to it on CD. I like the main theme and the wonderful

musicians but there are the scores of mine that I wouldn’t

listen to. I would listen to “Modigliani”. n, I sit here and

reflect, thinking: “Oh my God, I could have done better than

that!” The other strange thing is that, when you listen to

your work after you had a great experience writing, recording

and mixing it, you start questioning it. “Is it really that

good?” One or two years later, you get back to it and think:

“Wow, did I write that?” I do believe that if I can write a

few good pieces in every score, I am happy. There are pieces

in a score that just do their job because you are writing the

music for a picture and I don’t sit here writing a work by Guy

Farley: This is me, this is my concept, this is my work, I am

answerable to myself and that’s it. I am working on something

and I think about what the producers and the director said. I

am reacting to the picture I am looking at but I am

considering all these things and my music has to serve the

picture. I know people who wanted to release my score to

“Tsotsi”, which is such a very strong film and so

character-driven that I was never able to breathe or feel

free. So when you listen to the soundtrack you will notice

that everything I did was supporting a scene. That was the

reason why I decided not to release it because I wouldn’t want

to listen to it on CD. I like the main theme and the wonderful

musicians but there are the scores of mine that I wouldn’t

listen to. I would listen to “Modigliani”.

Q

:

”Modigliani” is interesting because the movie tries to

tell the story of the artist but can’t be accurate because of

the lack of information about Modigliani. The music fits quite

well to this approach in its concept because in some scenes

you used quite modern music with i.e. beat-boxing which didn’t

exist at the time the movie is set in. The music is not

authentic.

G.

F.:

That’s true. There weren’t any rules on it. It was a problem

though when it got released in France. There were people who

had a problem that the movie is presenting itself as a true

story when it wasn’t. They thought that a song like “La vie en

rose”, which was written 30 or 40 years later, shouldn’t have

been in the film. The director loved it. He loved what it did

to picture. If I was rescoring the film today, I would have

said: “Let me orchestrate ‘Clair de Lune’ for that scene”. For

the painting montage – which was totally made up – they wanted

this modern piece of music and I worked with the artist Sasha

Lazard, who has a beautiful voice, and we just went with it.

You have to make decisions and sometimes you get the things

right and sometimes you don’t. If you read some comments on

that sequence, there are some people who love it, who die for

it and then there are people who think it’s terrible and even

criminal because it ruins the whole film. I think most people

love it though. I had a rough time with that.

Q

:

But you agreed with that concept of using the beat-box

music?

G.

F.: What else could I

have done over that sequence?

Q

:

I found this montage with the modern music quite

distracting…

G.

F.: I

understand that but if I took that music out and you watch the

sequence you’d sit there and think: “Wow, this is like a

MTV-video” in the way it is cut and in the way it presents

itself. If it would have been cut in a different way, I could

have scored it. The thing is that there are no rules to film

music or even film making. Either it works or it doesn’t. One

of the luxuries a director has is he can put whatever music on

his movie that he wants: Woody Allen, Quentin Tarantino etc.

He can choose whatever he wants to. It’s not my favorite

sequence in the film. I took a song that the director liked

and remixed it in this studio but it was completely outside of

the score.

Q

:

So it was the director’s idea to take a modern piece

of music for that sequence?

G. F.: Yes

and do you know why? He said: “At the time, these people were

the most modern artists on the planet and I want to reflect

that what these guys are doing is what the most modern artists

are doing today. I want to reflect this modernity.” I don’t

know whether people buy that or not. The editor knew the

singer and so we ended up doing this song together. Actually,

we did two tracks for that sequence. “Modigliani” was a big

score to do and I was still relatively young and naive in

2004. I feel different today. I am a different person today. I

am more confident about my art. Confident enough to disagree

with a director and to say to him: “I don’t think this will

work and if you want this, maybe you should find somebody

else.” The one scene where they use “La vie en rose”, I’d

definitely say today: “Let me do an arrangement of Ravel or

Debussy because I think it would work better than a piece

which was written 30 or 40 years after the

event.”

Q

:

In the sequence where we can see Modigliani having

visions with people dancing in the streets and wearing masks,

we hear quite modern Avant-garde-music which sounds a bit like

Penderecki. However, you studied Penderecki first in 2008 for

“The Broken”, didn’t you?

G. F.: I am a huge fan of

Penderecki. I read a lot of those scores because the director

of “The Broken” said: “I want something very different here. I

don’t want traditional film music, I want you to do something

really different, using an orchestra.” Actually, I found more

inspiration in Penderecki than I did anywhere else and I

looked on a lot of modern composers like Boulez or Varese or

Schnittke. This was music that I had known before but never

really connected with.

What amazed me

was how totally open I was to everything they were doing. The

education I got from studying their scores was an education I

wouldn’t have got anywhere else. Studying the orchestration,

the sound-design that Penderecki created, gave me the first

idea and the original sound for my score that convinced the

director. For the scene in “Modigliani”, I just wrote the

music. I felt it and wrote it without having studied modern

music before. For “The Broken”, I wrote down certain sounds

that I had read and specific colors. It was all about

sound-colors and how to manipulate an orchestra. The most

exciting thing on “The Broken” was trying out things that I

had never done before with an orchestra and some cues I could

only write out by hand and give them to my orchestrator,

telling him what I’d like the orchestra to do and how the

musicians have to do it. It was extremely exciting doing it. I

remember writing one cue with bass harmonics on a cello,

playing wonderful clusters and we started rehearsing this cue

and I heard this sound and I couldn’t believe it. It was such

a beautiful sound! “Where does this sound come from?”

Q

:

You didn’t know how the music is going to sound when

you wrote it?

G.

F.: When

I wrote it, I was thinking about what I wanted the musicians

to do. I talked to a cellist about bass-harmonics and I had a

wonderful book here on bass-playing and so I invented these

certain clusters. Furthermore, I’d seen some very modern piece

of work performed on television. It was all about ice. All the

instruments reflected the ice. I remember that I loved that

sound. “The Broken” gave me the opportunity to try out all

these sounds. It is pure sound-design. It is hugely

interesting how you can take a single sound and do the

slightest thing to it and it affects somebody. Hans Zimmer did

a very clever thing in his score for “Batman” with the motif

for the Joker where the cello plays a single note which is

basically a very slow glissando.

Q

:

I thought it was very unusual to use Arabic

instruments in the setting of

“Modigliani”.

G.

F.: The

director said to me that Modigliani and Picasso are two

bullfighters. “Think about bullfighting with the Spaniard

Picasso and the Italian Modigliani.” I had seen the film “The

Sheltering Sky” which has a beautiful score by Ryuichi

Sakamoto, featuring a scene where the Arabs clap their hands

very fast. I loved the ancient sound of that. I decided to

write music that was a bit like Nomadic North African

campfire-music but something that built intensity. There are

two scenes in “Modigliani” where you hear the ethnic

percussion when Modigliani and Picasso are fronting each

other. They are stomping their hooves and snorting. I thought

it was a great way to express that musically. I also had an

Algerian singer who sang atop of the drums, the hand-clapping

and Arabic flutes and when we recorded it, everybody was

affected and aroused by the sound. I got it wrong though on

one cue that we threw out. In one scene, there is a fancy

Chinese dress party for which I used Taiko-Drums. Andy Garcia

took a great interest in the music and called me up every week

because he is very musical himself. I sent the cue with the

Taiko-Drums over to him and he said: “I think you have drawn

s o much attention to them

that we have lost the scene.” In the end, he was right.

However, I do think that the musical description of the

bullfight between Modigliani and Picasso worked. In general, I

wasn’t tied to things. The director had ideas, I had ideas. We

threw them in, we got rid of things that didn’t work and left

things in that he was happy to leave in. o much attention to them

that we have lost the scene.” In the end, he was right.

However, I do think that the musical description of the

bullfight between Modigliani and Picasso worked. In general, I

wasn’t tied to things. The director had ideas, I had ideas. We

threw them in, we got rid of things that didn’t work and left

things in that he was happy to leave in.

Q

:

Talking about another important movie in your career:

I watched “Cashback” last week and liked it very much as a

lovely, warmhearted, funny and melancholic piece of

work.

G.

F.: I loved working on

that movie! “Cashback” is another example of where my

relationship with the film was simply perfect. It all felt

right. The director, Sean Ellis, came to me and said he loved

the piece from “Modigliani” which is called “The Hat First”.

He asked me to write something like that. It’s like everybody

asking Thomas Newman “Can you write me something like a piece

from ‘The Shawshenk Redemption’? Can you write me something

like a piece from ‘American Beauty’?” and he ends up copying

himself. I can’t stand it when people temp their movies with

my music. I find it very difficult. There was something very

special about “Cashback”. I stood in this room and just wrote

the music. It was effortless. Think about all the music I

recorded for that movie: I wrote string arrangements for

modern songs, I arranged the aria “Casta Diva”, I wrote the

original score and we recorded all that in only four hours!

Q

:

I was quite surprised that you had enough money for an

orchestra because it is quite a small

movie.

G.

F.: Yes, I always

fight for an orchestra. Mark Isham wrote an amazing score for

“Crash” using his synthesizers. Lots of people can use

electronic instruments very well. I am a devout lover of

performers and instruments. Samples can’t play something that

sounds like a soaring violin-line. It doesn’t exist. I need a

room full of people that I can engage with, that I can watch

them pick up their bows, strike the strings, listen to the

sound of it and talk about it. I love

that.

CONTINUE TO PART

2 |

make sure that it

also makes a good listening-experience. “The Hot Potato” is a

very generic score because it has a sound from the 60s in the

style of John Barry or Henry Mancini. I loved writing that and

I knew what I was writing. I remember saying to the director

“If we were in 1968 and you would got John Barry to write the

score, that’s what I want it to sound like.” And the director

was absolutely crazy about that idea and let me do my thing.

make sure that it

also makes a good listening-experience. “The Hot Potato” is a

very generic score because it has a sound from the 60s in the

style of John Barry or Henry Mancini. I loved writing that and

I knew what I was writing. I remember saying to the director

“If we were in 1968 and you would got John Barry to write the

score, that’s what I want it to sound like.” And the director

was absolutely crazy about that idea and let me do my thing.

Q

Q

Q

Q

n, I sit here and

reflect, thinking: “Oh my God, I could have done better than

that!” The other strange thing is that, when you listen to

your work after you had a great experience writing, recording

and mixing it, you start questioning it. “Is it really that

good?” One or two years later, you get back to it and think:

“Wow, did I write that?” I do believe that if I can write a

few good pieces in every score, I am happy. There are pieces

in a score that just do their job because you are writing the

music for a picture and I don’t sit here writing a work by Guy

Farley: This is me, this is my concept, this is my work, I am

answerable to myself and that’s it. I am working on something

and I think about what the producers and the director said. I

am reacting to the picture I am looking at but I am

considering all these things and my music has to serve the

picture. I know people who wanted to release my score to

“Tsotsi”, which is such a very strong film and so

character-driven that I was never able to breathe or feel

free. So when you listen to the soundtrack you will notice

that everything I did was supporting a scene. That was the

reason why I decided not to release it because I wouldn’t want

to listen to it on CD. I like the main theme and the wonderful

musicians but there are the scores of mine that I wouldn’t

listen to. I would listen to “Modigliani”.

n, I sit here and

reflect, thinking: “Oh my God, I could have done better than

that!” The other strange thing is that, when you listen to

your work after you had a great experience writing, recording

and mixing it, you start questioning it. “Is it really that

good?” One or two years later, you get back to it and think:

“Wow, did I write that?” I do believe that if I can write a

few good pieces in every score, I am happy. There are pieces

in a score that just do their job because you are writing the

music for a picture and I don’t sit here writing a work by Guy

Farley: This is me, this is my concept, this is my work, I am

answerable to myself and that’s it. I am working on something

and I think about what the producers and the director said. I

am reacting to the picture I am looking at but I am

considering all these things and my music has to serve the

picture. I know people who wanted to release my score to

“Tsotsi”, which is such a very strong film and so

character-driven that I was never able to breathe or feel

free. So when you listen to the soundtrack you will notice

that everything I did was supporting a scene. That was the

reason why I decided not to release it because I wouldn’t want

to listen to it on CD. I like the main theme and the wonderful

musicians but there are the scores of mine that I wouldn’t

listen to. I would listen to “Modigliani”.

o much attention to them

that we have lost the scene.” In the end, he was right.

However, I do think that the musical description of the

bullfight between Modigliani and Picasso worked. In general, I

wasn’t tied to things. The director had ideas, I had ideas. We

threw them in, we got rid of things that didn’t work and left

things in that he was happy to leave in.

o much attention to them

that we have lost the scene.” In the end, he was right.

However, I do think that the musical description of the

bullfight between Modigliani and Picasso worked. In general, I

wasn’t tied to things. The director had ideas, I had ideas. We

threw them in, we got rid of things that didn’t work and left

things in that he was happy to leave in.